Despite my title, no, this entry is not about being a

woman in academia. Instead, it is about the topic of my dissertation:

eighteenth-century female cross-dressers.

If that sounds like a confusing mouthful, let me break it

down a little. First of all, literary studies of the eighteenth century focus

on a time period slightly longer than the actual seventeen hundreds. The Long

Eighteenth Century can encompass nearly 150 years, anywhere from 1660 to 1837,

with the ascension of Queen Victoria to the throne. My own dissertation takes

the Restoration into account, but most of the texts I analyze were written and

published roughly between 1700 and 1801—more true to the idea of the eighteenth

century I suppose. It may also be useful to mention here that my focus is on

British literature almost exclusively, despite the fact that there were women

dressing in men’s clothes all over Europe and North America at this time.

Probably in the rest of the world, too.

But I digress, as usual. Specifically, I am looking at

literary representations of women who wore men’s clothes, whether they are

actresses (who were finally allowed onto the English stage starting in 1660),

novel characters (usually ladies who dress in men’s clothes out of necessity or

pleasure), female soldiers (women who passed themselves off as men in order to

join the army or navy—these are historical figures), female husbands (women who

passed themselves off as men in order to seduce other women—usually their

stories are elaborations on facts), or female pirates (pretty

self-explanatory). Their stories were highly popular in the eighteenth century,

and some of the real life passing women were quite famous. Female soldier Hannah

Snell returned from duty, collected her pension, declared she was a woman, and

eventually performed military drills on stage in her uniform. You could even

buy a printed engraving of her to hang up on your wall if you so fancied.

Female soldiers like Snell were often considered heroes who virtuously

protected their female bodies from the sexual advances of men, showed

considerable bravery in the field, and were often thought of as even more

valorous than the men they fought alongside.

|

| Hannah Snell! Don't you just want her pic on your wall? |

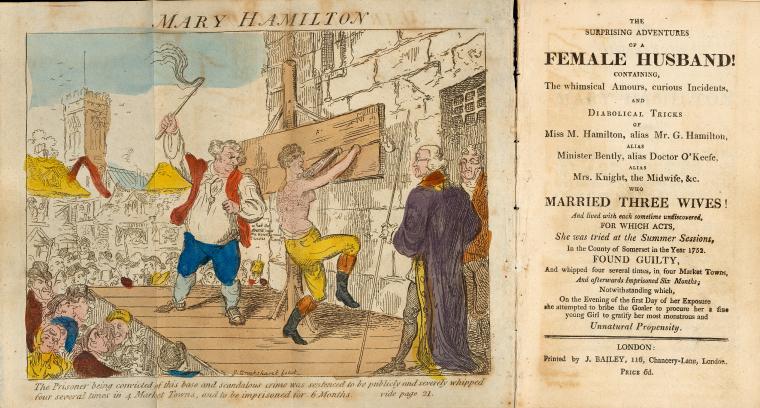

Female husbands, on the other hand, were considered

wicked cheats who pulled the wool over innocent women’s eyes, stole their

money, and maybe even indulged in unnatural pleasures with the help of a dildo

(not lying! It’s true!). These women were often castigated and, if caught, were

publicly whipped and/or put in prison for deception. Similarly, female pirates

Mary Reade and Ann Bonny cross-dressed in order to pillage and destroy as

pirates, and to have affairs with the dashing pirates they met (women were

often not allowed aboard ships for superstitions reasons. Also, being the only

woman aboard a ship full of sex-starved men was not a good idea either). These

women were also considered hussies and criminals.

|

| Female Pirates Ann Bonny and Mary Reade. |

|

| Showing leg was often associated with prostitution for women, as in this James Gillray print from the late 1700s. |

In my dissertation, I consider these representations as

part of a continuum. When I read more closely, I began to see a pattern in the

way that the cross-dresser’s body appeared in the texts. Eighteenth-century narrative

can be remarkably coy about people’s bodies; the cross-dresser’s body, which

would seem to be at the forefront of her story and how she manages her male

costume, only ever appears in fragments. The narratives I explore bring up

certain appendages or body parts only when there is a question about the

cross-dresser’s gender. In each chapter I explore a different appendage in

order to further establish how gender functions in the eighteenth century.

What has made my dissertation so much fun is exploring

precisely how eighteenth-century Brits felt about beards, breasts, penises,

dildos and legs, and then comparing those attitudes and cultural

representations to the representations in literature. Upon inspection, it

becomes clear that although many writers, physicians, moralists, newspaper

writers, and the general public felt that beards and penises denoted maleness

and breasts denoted femaleness, these assignments were not always so clear.

Although both men and women have legs, the texts I explore suggest that they

only signify sexually on women—even as their exposure comes primarily when

women don breeches.

|

| Actress Peg Woffington was famous for her "breeches parts" on stage. She often dressed in men's clothes to recite epilogues to plays, such as this one "The Female Volunteer." Sexy, eh? |

Ultimately, these appendages lose their ability to

signify one gender or another. The texts try to maintain gender dichotomies,

but cannot. Instead, their ambiguity becomes the way through which the

cross-dresser appeals to other women. Her body is at times exposed, at times

hidden, but either way, she is very attractive to other women. These

relationships between the cross-dresser and the women she comes into contact

with form the second half of my analysis. I argue that although not all the

relationships between the cross-dresser and her accomplices are sexual, there

is always a little bit of sexual tension—just enough that we, as readers, learn

how to read for these nuances. Call it eighteenth-century gaydar, if you will.

The cross-dresser’s gender-ambiguous body is attractive to and attracts other

women. Whether they know she is a woman or not doesn’t matter; the reader

always knows.

Whether she was on the stage, on a ship, or in another

lady’s bed, the female cross-dresser is an intriguing figure in the

eighteenth-century. In a time when readership is growing and women are

increasingly picking up paper and quill, the figure of the female cross-dresser

comes to represent the freedoms and restraints that women of the time faced.

This is not to say that there weren’t other kinds of women who tested the boundaries

of social norms, or other kinds of women who engaged in Sapphic practices…it’s

just to say that our understanding of women’s lives and desires, and their

representations in literature, are incomplete until we look a little more

closely at the female cross-dresser.

|

| Female Husband Mary Hamilton from Fielding's The Female Husband gets whipped in punishment for her crimes. |

No comments:

Post a Comment